7th Schedule of Indian Constitution: Union, State & Concurrent Lists

Polity

UPSC Prelims

Current affairs

Latest Update

Gajendra Singh Godara

Oct 22, 2025

15

mins read

The Seventh Schedule is the legislative blueprint of India’s federal system, dividing law-making powers between the Union (Central) and State governments. It categorises subjects into three lists – the Union List, the State List, and the Concurrent List – so that each level of government knows which subjects it can legislate on. This clear division of subjects is crucial for balance in India’s quasi-federal setup.

What is the 7th Schedule? It is Part XI (Articles 246–255) of the Constitution that lists subjects for the Union, States, or both. It concretely allocates legislative powers in a federal system.

Why it matters: It forms the backbone of Centre–State relations by clarifying who makes laws on what. This prevents conflicts and ensures unity in crucial areas while allowing diversity where needed.

Example: Under the 7th Schedule, defence falls in List I (Union), police in List II (State), and education in List III (Concurrent).

Historical Evolution of 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

The idea of dividing legislative powers comes from India’s colonial past. The Government of India Act of 1935 created three lists of subjects. These are the Federal List, Provincial List, and Concurrent List.

When India became independent, the writers of the Constitution created a similar plan in 1950. They renamed the lists as List I, II, and III.

They balanced India's diversity with national unity. The Centre was given power to keep the country together. At the same time, States were allowed to manage local matters.

The purpose of the Constituent Assembly was to create three lists. The framers wanted a balance of power.

National matters would be under Union control. Regional matters would be under State control. Shared matters would go on the Concurrent List.

In the Constituent Assembly debates, members stressed unity in diversity. The Seventh Schedule was created to allow states to have their own policies on local issues. This helps keep the nation united.

India is often described as quasi-federal with a unitary bias. Unlike some federations (like the US), the Constitution of India allows the Centre to intervene under certain conditions.

The Seventh Schedule came from colonial laws. India’s founders changed it to fit a new, diverse nation. It protects the federal nature of the Constitution. However, Articles 249 to 254 allow the Centre special powers during emergencies or for national interest.

Constitutional Basis and Legislative Jurisdiction

Article 246 : Distribution of Powers

Article 246 of the Constitution spells out how legislative powers are divided by referring to the Seventh Schedule lists:

Clause (1): Parliament has exclusive power to legislate on subjects in the Union List (List I). This means only the Union government can make laws on these matters.

Clause (2): Both Parliament and State Legislatures can make laws on subjects in the Concurrent List (List III). Both levels can legislate; if there is a conflict, the Union law generally prevails.

Clause (3): State Legislatures have exclusive power on subjects in the State List (List II). Only States can make laws on these subjects, under normal circumstances.

Clause (4): Parliament may also legislate on State List subjects when it concerns Union Territories (UTs). Union Territories like Delhi and Puducherry do not have full State governments. So, the Union Parliament makes laws on matters that are usually for States.

If a state law goes against a Union law on a shared topic, the Union law will take priority. This is according to Article 254.

For example, Article 247 and the Seventh Schedule show that certain areas are only controlled by the Union. These areas include defense, currency, atomic energy, and foreign affairs.

In contrast, entries like public order, local government, land, agriculture are reserved for State legislatures alone. Article 246 ensures a clear demarcation so that each level of government knows its legislative boundary.

Article 248 and Entry 97

The Constitution also provides for residuary subjects matters not mentioned in any of the three lists. Article 248 assigns all residuary legislative powers exclusively to Parliament. This means that if a new issue or unlisted topic arises (for example, cyber security, digital currency or space exploration), only the Central Parliament can make laws for it.

Residuary powers make sure that new or unexpected areas are handled at the national level. This shows a strong central focus in our federal system. For example, the Internet and AI were not anticipated when the Constitution was written. However, Parliament can make laws about these topics since they are not listed specifically.

The Centre has the final decision on matters not covered by the original Seventh Schedule. This is stated in Article 248 and Entry 97 of the Union List.

Related Articles (249–254) affecting the 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

Several other articles of constitutional provisions modify how the Seventh Schedule operates:

Article 249:

Should the Rajya Sabha achieve a 2/3rd majority vote, it can declare a significant matter for the nation. Afterward, Parliament has the authority to make laws on any State List topic.

The law applies to the whole or any part of India. Example: Parliament once used this to enact laws on health and labour issues that affected all states.

Article 250:

During a national emergency, Parliament can make laws on State List subjects for all or part of India. This can happen even without a Rajya Sabha resolution.

Since emergencies suspend normal federal arrangements, the Centre assumes extra powers, including in areas normally reserved for States.

Article 252:

If two or more State Legislatures request it, Parliament can legislate on State List matters common to those States. The resulting law applies only to those States, but other States may adopt it later.

This allows cooperation among States , for example, if neighboring states face a common issue like river water sharing, they can ask Parliament to pass a law.

Article 253:

Parliament can legislate on any matter (including State List subjects) for implementing treaties, international agreements, or decisions of international bodies.

For instance, if India signs an international environmental treaty, Parliament may make laws on related subjects even if they are ordinarily state concerns.

Article 254:

If a State law on a Concurrent subject conflicts with a Central law, the Central law prevails to the extent of repugnancy.

If the State law is passed and gets Presidential approval, it can stand in that State. This is true unless Parliament cancels it later.

In practice, this means that Union laws on Concurrent subjects usually take priority over state laws. There are rare exceptions when a state law is specifically allowed to remain.

These articles introduce flexibility: in national crises or agreements, the Centre can momentarily step into areas of State jurisdiction. However, Article 254 enshrines the supremacy of Union laws over conflicting State laws on shared subjects.

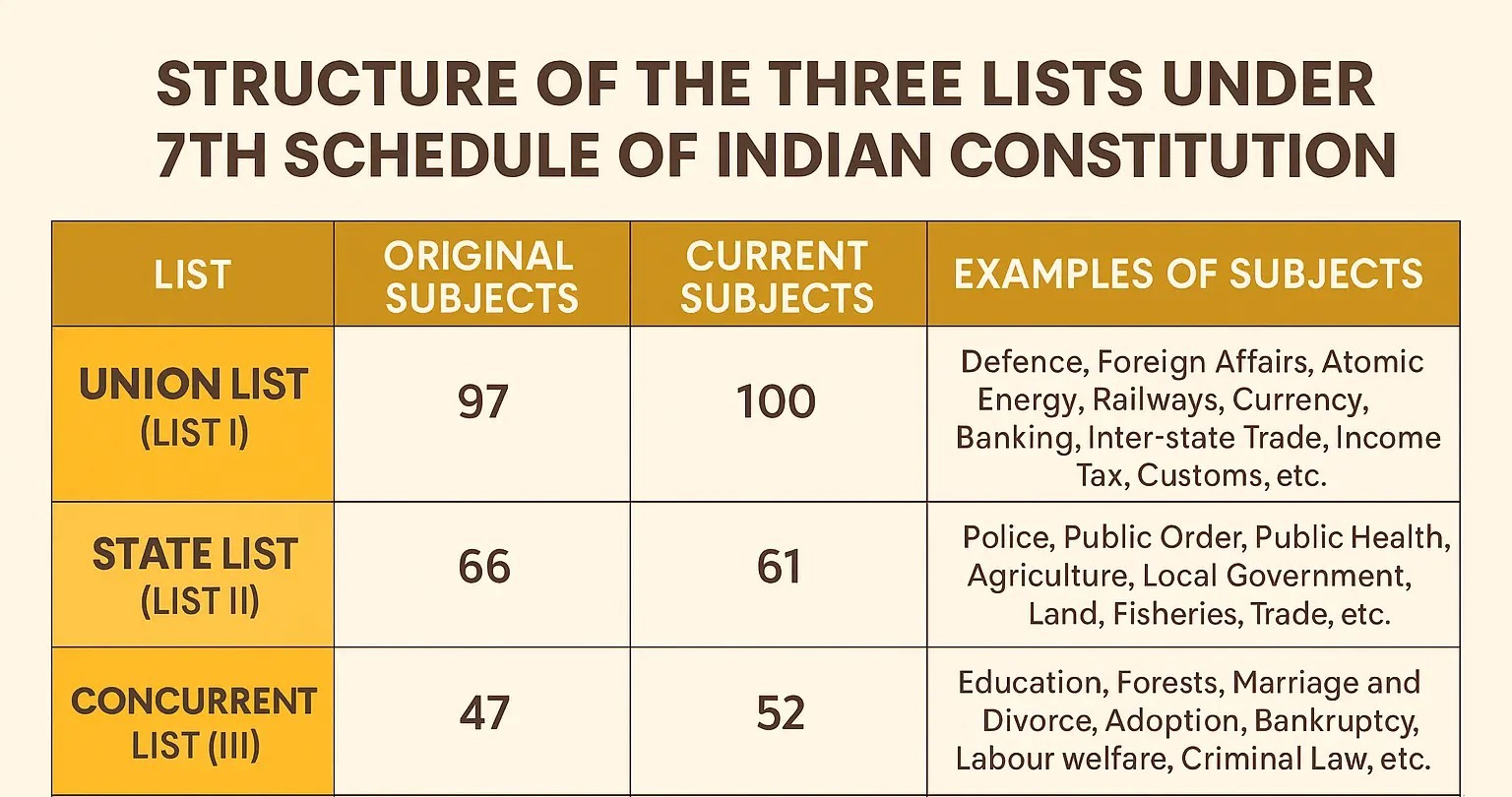

Structure of the Three Lists under 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

List | Original Subjects | Current Subjects | Examples of Subjects |

Union List (List I) | 97 | 100 | Defence, Foreign Affairs, Atomic Energy, Railways, Currency, Banking, Inter-state Trade, Income Tax, Customs, etc. |

State List (List II) | 66 | 61 | Police, Public Order, Public Health, Agriculture, Local Government, Land, Fisheries, Trade, etc. |

Concurrent (List III) | 47 | 52 | Education, Forests, Marriage and Divorce, Adoption, Bankruptcy, Labour welfare, Criminal Law, etc. |

The table above compares the three lists under the Seventh Schedule. Originally there were 97 Union List items, 66 State List items, and 47 Concurrent List items. Constitutional amendments, notably the 42nd and 101st, have changed these counts to the current totals.

Union List (List I)

Scope and Count: The Union List contains subjects of national importance. It had 97 entries at the Constitution’s inception and has about 100 today.

Exclusive Powers: Only Parliament can make laws on Union List subjects. State legislatures cannot legislate on these at all. This centralizes control over critical areas.

Significance: The Union List includes the most important subjects. It shows the Centre's strong role in the federal system. It ensures uniformity: a law enacted here applies equally across India.

The Centre can also delegate or authorize states to act in some Union domains if needed (e.g. a central law may allow states to run certain defense factories under its oversight).

State List (List II)

Scope and Count: The State List originally had 66 entries, now 61 (five subjects were shifted out by the 42nd Amendment).

Exclusive Powers: Under normal conditions, State Legislatures can alone legislate on these subjects. For example, only a state can regulate its police force or build local roads. States also have the power to levy certain taxes on State List items.

Limitations & Exceptions: There are special cases. For instance, Article 249, 250, 252 allow Parliament to legislate here under the circumstances explained above.

Also, by Article 239AA (as inserted by the 69th Amendment), Delhi’s elected government is barred from making laws on three core State subjects: police, public order, and land. These remain with Parliament because Delhi is a Union Territory with a special status. (Puducherry has a similar arrangement for certain entries.)Significance: The State List empowers local governance and regional diversity. It ensures that states can tailor laws to their unique needs.

For example, states can legislate differently on irrigation or local roads to suit geography. However, because India’s Constitution provides central checks (like emergency powers), state autonomy here is balanced by national interests when necessary.

Concurrent List (List III)

Scope and Count: The Concurrent List started with 47 subjects. It now has 52 entries. This change happened after the 42nd Amendment added five subjects from the State List. It includes areas where national uniformity is desirable but not essential.

Shared Powers: Both Parliament and State Legislatures can legislate on these subjects. For example, both can make laws on education or forest conservation. Often, states enact legislation adapted to local conditions, while Parliament may pass more general laws.

Conflict Rule: When both levels legislate on a Concurrent subject, Article 254 governs conflicts. If a State law conflicts with an existing Central law, the Central law prevails.

The only exception is if a State law received the President’s approval. If Parliament has not overruled it, that State law can remain in effect. In practice, most concurrent conflicts are resolved in favor of the Centre.

Significance: The Concurrent List fosters cooperation. It allows States to address important areas (like social welfare) while preserving national standards.

For instance, before the National Education Policy, many education regulations were state-specific. Now, with a law like the RTE Act (Right to Education), there are consistent schooling standards across India.

The three-list structure, along with Articles 246–254, creates a clear framework. The Union manages all central subjects. States take care of local matters. Many broad subjects are shared to allow for flexibility.

Amendments Affecting the 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

Over time, the Seventh Schedule has been modified by constitutional amendments to reflect changing needs:

42nd Amendment Act (1976): This was part of a larger set of changes during the Emergency period. It shifted five key subjects from the State List to the Concurrent List. The transferred subjects were:

Education (except technical education)

Forests (Entry 17 originally on State List)

Protection of wild animals and birds (Entry 17A)

Weights and Measures (Entry 33)

Administration of Justice, including the organization of all courts except Supreme Court and High Courts (Entry 4)

The effect was to enlarge the Centre’s legislative domain, since now both Centre and States could make laws on these areas. In practice, Parliament took on major roles in education (e.g. later RTE Act) and forest conservation (Forest Conservation Act).

This amendment led to debates about state autonomy. However, its changes are still in effect. Education and forests remain concurrent.

101st Amendment Act (2016 – GST): Introduced the Goods and Services Tax (GST), a unified indirect tax. Its impacts on the Seventh Schedule were:

A new Article 246A has been added. It gives Parliament and State legislatures the power to levy GST. This applies to supplies of goods and services.

Removed or amended the specific entries in the State List related to sales tax on goods (since GST subsumed those taxes).

Constitutionally recognized the GST Council (though not in the Schedule) as a federal mechanism for tax decisions.

As a result, India moved to a single indirect tax regime. The amendment reduced the state's control over sales taxes, which are now shared. It aimed to improve cooperation between states and the federal government through the GST Council.

These amendments show that the lists are not fixed forever. The Constitution lets the Centre and States change the division of powers together. They can do this through amendments. This way, the laws can adjust to new economic or social policies.

Significance of 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

Clear Division of Powers: The Seventh Schedule clearly divides legislative topics between the Union and States. This ensures clear law-making and prevents overlap in authority.

Federal Balance: It keeps a balance between central control and state independence. The Centre deals with national issues, while States handle local matters.

Promotes Cooperative Federalism: By defining roles, it fosters coordination rather than conflict between different levels of government.

Flexibility through Concurrent List: The Concurrent List enables both Centre and States to legislate on shared subjects, ensuring adaptability to emerging policy areas.

Ensures National Unity and Integrity: Strengthens India’s unity by empowering a strong central authority while safeguarding the States’ constitutional role.

Way forward for 7th Schedule of Indian Constitution

In over seventy years, India’s political, economic, and administrative landscape has changed a lot since 1950. The Seventh Schedule now needs a fresh look to reflect these realities.

Changing Governance Needs: Governance priorities in 1950 differ greatly from today. Subjects like digital economy, climate change, and AI regulation didn’t exist then but now require clear jurisdictional authority.

Trend of Centralisation: Constitutional amendments have gradually shifted several subjects from the State List → Concurrent List → Union List, concentrating more powers at the Centre.

The 42nd Amendment in 1976 was a major change. It moved education, forests, and weights and measures to the Concurrent List. This showed a clear move towards centralization.The Rajamannar Committee's Concern (1971): The Committee asked for a High-Powered Commission of experts. They wanted this group to look again at the entries in List I and III. They suggested redistributing them to restore balance between the Centre and the States.

Uneven Development Across States: India’s States differ in their levels of industrialisation and labour markets.

Uniform laws on land, labor, and natural resources may not work for all states. This has led to many debates.Under-examined by Commissions: Commissions on Centre-State relations (like Sarkaria, Punchhi) mostly focused on Article 356 or financial relations, while the Seventh Schedule rarely received independent scrutiny — a gap that needs correction.

Strengthening Federalism: Decentralisation allows better policy innovation, quicker local responses, and deeper accountability - all vital for cooperative federalism in a diverse country like India.

UPSC Previous Year Questions

Q. Which one of the following statements is correct as per the Constitution of India? (2024)

Inter-State trade and commerce is a State subject under the State List.

Inter-State migration is a State subject under the State List.

Inter-State quarantine is a Union subject under the Union List.

Corporation tax is a State subject under the State List.

Answer: (c)

Q. Which of the following provisions of the Constitution of India have a bearing on Education? (2012)

Directive Principles of State Policy

Rural and Urban Local Bodies

Fifth Schedule

Sixth Schedule

Seventh Schedule

Select the correct answer using the codes given below:

1 & 2 Only

3, 4, & 5 Only

1, 2 & 5 only

1, 2, 3 ,4 & 5

Answer: (d)

The Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution is fundamental to our federal democracy. It explains who makes laws on different topics. This keeps a balance between a strong central government and independent States. By clearly enumerating Union, State, and Concurrent powers, it prevents confusion and conflict in legislative functions.

However, the Seventh Schedule must continue to evolve. As India improves its governance and technology, officials can update the Seventh Schedule. This will help keep legislative powers fair and relevant. But its core idea a clear, written division of powers remains a cornerstone of Indian federalism.

For UPSC aspirants and policymakers, understanding the 7th Schedule is important. It helps them see how India’s Centre State relations work and how they can improve over time.